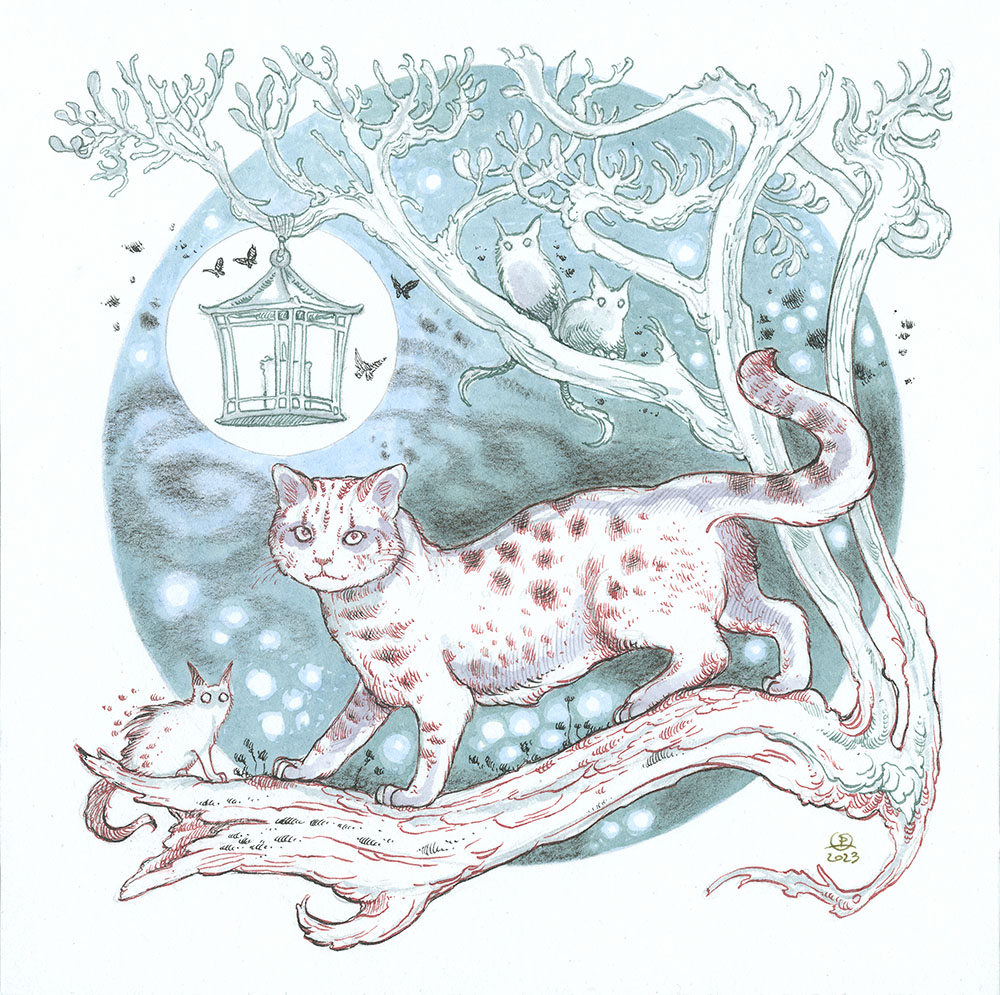

Scientific Name: Prionailurus bengalensis euptilurus

Status: Endangered. Population in decline due to habitat degradation and road kills.

In Japanese folklore there is a supernatural feline entity called bakeneko, meaning "changed cat". These spirit cats possess shape-shifting abilities that allow them to disguise themselves as smaller harmless housecats, or as humans. They can be fond of wild dancing and carousing, but they are equally drawn to malicious tricks, impersonating humans for dark ends, and bringing about curses and misfortune.

Cats can become bakeneko after they have sufficiently aged, twelve or thirteen years, and their tails become extra long as an indication of their supernatural identity. They are attracted to lamps and can be found licking lamp oil (fish oil was often used in lamps, in rural areas).

References:

Krenner, W. G. v., Jeremiah, K. (2016). Creatures Real and Imaginary in Chinese and Japanese Art: An Identification Guide. United States: McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers. 98-101.

Paget, R. (2023). Divine Felines: The Cat in Japanese Art: With Over 200 Illustrations. (n.p.): Tuttle Publishing. 114-126.

Scientific Name: Gavia adamsii

Status: Near Threatened due to much of their population residing in areas that have been opened to oil and gas development in Alaska, and a slightly declining population.

The mournful and beautifully poignant cry of the loon can be heard skimming across the waters at dawn and dusk. The Tsimshian people who live in Canada and Alaska have a story of how the loon got its white necklace of feathers. Loon assisted a blind man, restoring his vision by taking him under his wing and swimming swiftly under the mirror clear waters of a lake. After several circuits of the lake, when Loon and the man emerged, his sight was restored. He gifted Loon his traditional Tsimshian necklace, and it melted across Loon's neck to create the white pattern of feathers around the bird's ruff.

References:

Spencer, R. F., & Carter, W. K. (1954). The Blind Man and the Loon: Barrow Eskimo Variants. The Journal of American Folklore, 67(263), 65-72.

Native American Tales and Legends. (2012). United States: Dover Publications.

The Cry of the Loon: https://uaf.edu/ankn/publications/collective-works-of-angay/The-Cry-of-the-Loon.pdf

Scientific Name: Mandragora turcomanica

Status: Fewer than 500 plants found in the limited native range of Turkmenistan and mountainous Iran.

Mandrake grows in the mountains of Turkmenistan with delicate flowers of purple born up on slender stalks in the springtime. But the plant is known more for what lies beneath the soil, in the roots that can be narcotic and hallucinogenic. The branching bulbous roots have a visual similarity to the human form. That eerie resemblance made the mandrake the source for a large body of superstitions, and inspired beliefs of occult powers. It was said to be a particularly favored plant for sorcerers and witches. Pliny, natural philosopher of ancient Rome, said that a black root was shaped as a woman, and white root was shaped as a man.

It was said the plants sprang forth from the blood dripping from a hanged man, and that to pull a mandrake from the earth without proper preparations would elicit a scream from the plant, causing paralysis, madness, and death to those who heard. For centuries mandrake was much sought after as a luxury item, because of its use as a powerful magical ingredient used in spells and charms to induce fertility, to grant wealth and power, or to control destiny. It was sometimes called Devil's Apple, for its use as an aphrodisiac and love charm.

Medicinally, it was mixed with morphine to induce "twilight sleep", but was dangerous in too large a dose. The symptoms of such, were that which the myths claimed would occur to those foolish enough to dig up the plant without proper knowledge of the lore.

References:

Taylor, B. (1900). Storyology: Essays in Folk-lore, Sea-lore, and Plant-lore. United Kingdom: E. Stock. 78-90.

Watts, D., Watts, D. (2007). Dictionary of Plant Lore. Netherlands: Elsevier Science. 239-241.

Folkard, R. (1884). Plant Lore, Legends, and Lyrics: Embracing the Myths, Traditions, Superstitions, and Folk-lore of the Plant Kingdom. United Kingdom: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington. 425-429.

Scientific Name: Varanus mabitang

Status: Endangered. Highly dependent on forest ecosystems, and their habitat is fragmented and disappearing and they are also threatened by hunting

In the Philippine, the Bagobo tell a story of how monitor-lizard and chameleon (in the indo-Malaya this would be the common garden lizard, Calotes versicolor) got their respective markings. The two reptiles one day decided they would scratch patterns onto one anothers' backs. Monitor-lizard went first, scratching an elaborate, carefully even pattern on chameleon's back. When it came time for chameleon to do the scratching, the two were started by the sound of a hunter and dog. Fearfully, chameleon continued some erratic scratching, but at last lost his nerve, and with his final scrabbling cut short, he turned tail and ran. This is why chameleon has a beautiful design on his back, while monitor lizard's is wrinkled and erratic looking.

References:

Benedict, L. W. (1913). Bagobo Myths. The Journal of American Folklore, 26(99), 13-63. https://doi.org/10.2307/534786

Ho, T. (1967). A Comparative Study of Myths and Legends of Formosan Aborigines. (n.p.): Indiana University.

Scientific Name: Synallaxis infuscata

Status: Endangered due to disappearing habitat of their tiny range in Atlantic Forest of Brazil. Forest clearance and disturbance is their largest threat.

In the Amazon jungle, Pinto's spinetail is a foraging brown and grey bird. There is a Tupi legend of a bird that they call jurutahy. It is said to be brown and ugly. This poor bird looked upon the moon and fell in love with her glowing visage, and so he courted her, singing love songs indefatigably through the long nights. Despite his ardent musical proclamations, the moon scorned the little bird, night after night. His entreaties fell upon her beautiful and deaf ears.

The jurutahy is thus seen as a symbol of the romantic bliss that a poet experiences. Though the world might not care for his artistry, still he creates, still he sends his voice out into the void, for to speak of love is worthwhile in itself.

References:

Figueira, G. (1942). Mythology of the Amazon Country. Books Abroad, 16(1), 8-12. https://doi.org/10.2307/40082369

America indigena: organo oficial del Instituto Indigenista Interamericano. (n.d.). Mexico: Instituto Indigenista Interamericano. 41-42.

Scientific Name: Sciurus vulgaris

Status: Near Threatened in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Population has been declining for decades since the introduction of invasive grey squirrels from America. Grey squirrels carry and spread a virus that they are themselves immune to, but for which red squirrels have no defense. They are also threatened by increased road traffic and predators.

In Norse mythology, the world tree is a great ash tree named Yggdrasil. Its branches, trunk, and roots span all of creation, both the earth, hell, and the heavens. All the mortal realm, and that of the gods in encompassed in its being.

The ancient Norse book, Prose Edda, was written in the 13th century. The prose Edda recounts how in the crown of the tree is a wise eagle, keen-eyed and far-seeing. On one of the tree great roots is a dragon, who bites and tears at the tree. In the space between, constantly running up and down the trunk, there is a squirrel named Ratatoskr. He scurries back and forth, between the eagle in the upper aeries, and the dragon in the lower roots. He is a messenger, relaying their ancient enmity with mischievous delight. With chittering words, the squirrel nips at the edges of the feud to sustain it. With his drill-sharp teeth he gnaws at Yggdrasil, a part of the endless destruction and regrowth of the great ash.

References:

Hagen, S. N. (1903). The Origin and Meaning of the Name Yggdrasill. Modern Philology, 1(1), 57-69.

Byghan, Y. (2020). Sacred and Mythological Animals: A Worldwide Taxonomy. United States: McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers. 161.

Wood, F. T. (1942). GRIMNISMAL 33. Scandinavian Studies, 17(3), 110-113.

Scientific Name: Cephalophus zebra

Status: Vulnerable due to deforestation, loss of habitat, and overhunting.

Duikers are small antelopes living in the savannas and shrublands of sub-Saharan Africa.

A Bassari creation story tells of the origin of languages. The creator Unumbotte first made Man, and named him. He subsequently made and named Antelope, and Snake. Unumbotte had the three of them pound the earth, then gave them three seeds to plant in the newly smoothed earth. From this seed sprang a palm tree with red fruit. Every seven days Unumbotte came to the tree and collected the fruit. The man, antelope and snake did not eat from the tree, but the snake started to ask the man, "Why don't you eat the fruit?" At first the man did not heed the snake, but eventually he gave in and plucked and ate from the tree.

When Unumbotte returned, he saw that the fruit had been consumed. When asked if they had done so, the man spoke up and said that he had been hungry, and the snake had told him to eat. Unumbotte gave to man grains and roots to grow and harvest. When asked, the antelope said he had not, that when he was hungry he had simply eaten the grass at the base of the tree. Unumbotte set the antelope on the wild fields then, and gave him all the grass to eat. For the snake, whose words had urged the man to eat the fruit, Unumbotte gave poison and fangs with which to bite people. The men who ate from the same bowl, gathered and spoke the same language, and those that ate from other bowels spoke other languages and traditions.

References:

Oxford Reference: Unumbotte and the Origin of Languages (Bassari/Togo) in A Dictionary of African Mythology

Ford, C. W. (2000). The Hero with an African Face: Mythic Wisdom of Traditional Africa. United Kingdom: Random House Publishing Group. 174-175.

Witzel, M. (2012). The Origins of the World's Mythologies. United Kingdom: OUP USA. 365.

Scientific Name: Cuon alpinus

Status: Endangered. Dhole have a wide range, that stretches across Siberia, India, Java, Sumatra, and China. Though they only rarely attack domestic livestock, they were still hunted and killed to protect livestock, and for the belief that they were responsible for diminishing game populations. As large predators they are crucial in regulating healthy populations of smaller mammals and reptiles.

Huli, fox spirits, appear throughout folktales China. They were supernatural shape-shifters, that sometimes appeared as a man or woman, bewitching those that they came across. They were both feared, as well as worshiped and given offerings at shrines to maintain their appeasement and good will. The stories are full of benevolent fox spirits bestowing good fortune and wealth, as well as malicious and vindictive ones.

There are legends that foxes haunt old temples, abandoned shrines, and graveyards, living amongst ghosts. They dig up skulls and place them upon their bodies and perform obeisance towards the North Star. If the skull does not fall off, they then are transformed into a beautiful human.

Huli jing were fox spirit women, or a human woman who was possessed by or under the influence of a fox spirit. In encounters with humans, they invariably, sometimes unintentionally drew out the life-force of their consorts, in a way that was similar to how ghosts hungered for the sustaining energy of a living spirit. Foxes desired this energy for the purpose of aiding their quest for immortality and achieving unity with the dao. Occasionally they would feel remorse and heal those victims as well, returning that absorbed energy. Daji, a famously cruel and malevolent concubine of the last king of the Shang Dynasty in ancient China, was said to have been possessed by a fox spirit.

References:

Stevens, K. (2013). Fox Spirits (Huli). Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch, 53, 153-165.

BURKHARDT, V. (1972). Chinese Creeds and Customs: Volume 3. Hong Kong: South China Morning Post.

Johnson, T. W. (1974). Far Eastern Fox Lore. Asian Folklore Studies, 33(1), 35-68.

Hammond, C. E. (1996). Vulpine Alchemy. T'oung Pao, 82(4/5), 364-380.

Scientific Name: Equus ferus przewalskii

Status: Endangered. Nearly went extinct but captured populations were part of breeding programs and have been grown to where they are being reintroduced into the wild in protected areas, however they still have many obstacles to recovery due to the very small gene pool that was used to repopulate.

In Mongolian culture, horses occupy an honored place as an integral part of life. Wild horses are revered as the riding mounts of the Gods. They are holy, and called takhi, which means "spirit" in Mongolian. Great herds of Mongolian Wild Horse once roamed the steppes, and they are often found in Mongolian folktales and legends as fiercely spirited and majestic beasts. In some tales, they are gifted with wings and flight and are worthy companion to heroes. White horses are seen as especially spiritual, and shamans and khans are the only ones who rode upon them.

References:

Schaller, G. B. (2020). Into Wild Mongolia. United Kingdom: Yale University Press.

Fijn, N. (2015). The domestic and the wild in the Mongolian horse and the takhi. In A. M. Behie & M. F. Oxenham (Eds.), Taxonomic Tapestries: The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research (pp. 279-298). ANU Press.

Scientific Name: Panthera leo leo

Status: Small groups of the Egyptian lion were surviving in Algeria and Morocco until the mid-1960s, but were hunted to extinction in the wild. A few still remain in captivity.

In ancient Egyptian mythology, the lion was often used in sun-symbolism. They were often associated with the solar aspects of dieties, and sometimes depicted with a sun disk behind their heads.

Aker was the god who guarded the horizons. These are the eastern and western entrances to the underworld. He was responsible for the gateway to the earth, and was the the boundary that lay between these transitional times. In iconography, he is represented as a thin strip of land and horizon, with the sun's orb glowing above, and two guardian lions facing away from each other at either end. These two lions were named Tuau (today) and Sef (yesterday). They guarded the morning gate, and the evening underworld gate. Aker was also sometimes represented with two lino heads, or as a double-sphinx.

References:

Hellinckx, B. R. (2001). The Symbolic Assimilation of Head and Sun as Expressed by Headrests. Studien Zur Altagyptischen Kultur, 29, 61-95.

Strawn, B. A. (2005). What is Stronger Than a Lion? Leonine Image and Metaphor in the Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East. Germany: Academic Press. 200-203.

Muller, W. M., Scott, J. G. (1918). Egyptian [mythology]. India: Marshall Jones Company. 41-44.

Scientific Name: Athene blewitti

Status: Endangered due to loss of forest habitat. The forest owlet is endemic to India, and it was thought to be extinct from the late 1800s, but in recent decades has been occasionally sited. Because of the superstitions associated with owls and their link with Lakshmi, owls have been captured and sacrificed for the sake of good fortune and prosperity during the Hindu celebration Diwali, "festival of lights".

Owls in India have often been hunted for both the good and the ill omens that folklore assigns to them. They are illegally hunted and traded, often sacrificed to ward off the evil eye that is associated with them, as well as to boost wealth and fortune on auspicious celebrations.

Lakshmi is the goddess of wealth, fertility, and power. In iconography, she is usually seated or standing on a lotus, with her elephants, or else with an owl. The owl is a symbol of foretelling, perception and knowledge, patience, and wisdom. As a creature of the night, it is also a reminder to not be blinded by bright splendor of the trappings of wealth, but to seek for deeper spiritual wealth.

Her twin sister and diametric opposite, is Alakshmi. Alakshmi is everything that Lakshmi is not. She is misfortune, strife, calamity, envy, greed, war.

References:

Mohanty, S. (2009). Book of Kali. India: Penguin Books Limited.

Flibbertigibbet. (1966). The Goddess and the Owl. Economic and Political Weekly, 1(12), 484-85.

Gupta, Kriti. (Oct 2018). How India Is Losing Endangered Species Of Owl To Black Magic Rituals During Diwali. India Times.

Abul Bashar, Dutta, K., & Robinson, A. (2007). Rebirth. Manoa, 19(1), 187-192.

Scientific Name: Eidolon helvum

Status: Near threatened. Though it is common throughout its range of sub-Saharan Africa, it is hunted as bushmeat, and its population has been declining.

A story from Sierra Leone explains how darkness and cold came into the world. When the earth was first made, the sun and moon shone in alternating cycles, bathing the world in their light at all times. One day God summoned Bat to him and entrusted Bat with a package of darkness that he was to bring to the moon. Bat did not realize the importance of his task, and so he was careless. Midway through his journey, he grew hungry and paused on the road. He set down the package to flit into the trees and find fruit to eat. The other animals, mischievous and curious, saw the abandoned item and began tugging at the strings that bound it shut. Too late, Bat saw what was happening, and though he rushed forth to scatter the interlopers, it was too late. The last string was pulled loose and darkness flowed out into the world. Bat tried desperately to catch the darkness, flitting this way and that way, but it was to no avail. Exhausted, he fell asleep, only to wake at the next twilight and once again attempt his hopeless task of catching the darkness in order to put it back and take it to the moon. This is why you often see bats fluttering in the twilight hours, forever trying to catch the darkness.

References:

From African Myths, General Ed: Jake Jackson 2019 Flame Tree Publishing Ltd.

Andrews, T. (2000). Dictionary of Nature Myths: Legends of the Earth, Sea, and Sky. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. 52, 136.

The Langston Hughes Review: Official Publication of the Langston Hughes Society. (1992). United States: Afro-American Studies Program, Brown University. 46.

Scientific Name: Bos gaurus

Status: Vulnerable, threatened by poaching for meat and trophies.

The Hindu god Indra is god of the heavens, rain, and fertility. He has power over storms and the sky. He is called "lord of the water-givers." The clouds are his herds of cattle. When lightening splits the heavens, it is evidence of the battles Indra wages to protect the celestial beasts from being stolen by drought demons. Their bellows make the earth tremble, and can be heard in the great crashing of thunder, and the sound of their hooves across the sky presage rainstorms. When the land becomes parched, and the green hills shrivel to golden dust with thirst, Indra brings forth the herds to rain nourishment, fill the rivers, and grant life.

References:

Rig-Veda-Sanhita: A Collection of Ancient Hindu Hymns ... (1850). United Kingdom: W. H. Allen and Company.

Majupuria, T. C. (1991). Sacred animals of Nepal and India: with reference to Gods and Goddesses of Hinduism and Buddhism. India: M. Devi. 91.

Andrews, T. (2000). Dictionary of Nature Myths: Legends of the Earth, Sea, and Sky. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. 178.

Hopkins, E. W. (1916). Indra as God of Fertility. Journal of the American Oriental Society, 36, 242-268.

Scientific Name: Ursus arctos isabellinus

Status: Vulnerable. Poached for fur and claws. Also killed by shepherds protecting their domestic livestock.

Unexplained tracks, and distantly glimpsed sightings have long given rise to legends of yeti in the Himalayan mountains. Arguments rage on whether anecdotes of yeti sightings are the result of hallucinations brought on by the high altitudes and cold, or the misinterpreted silhouette of a bear standing upright, or that it is an elusive and shy actual creature, or an outright hoax.

The word "yeti" stems from the Tibetan word yeh, meaning "rocky area", and teh denotes an animal. The yeti is said to be seven or eight feet tall, bipedal ape-or-bear-like creature. Color of the fur ranges from white and grey to brown. Many hair samples and mummified remains have been collected over the years that was attributed to the yeti, however when scientific analysis was performed on these samples, the large majority of the results pointed to the Himalayan brown bear.

The Sherpa people of Nepal and Tibet tell of a related creature called dzu-teh. Although it is also larger even than the yeti, with long shaggy hair, and it is primarily quadrupedal.

References:

Forth, G. (2008). Images of the Wildman in Southeast Asia: An Anthropological Perspective. (n.p.): Taylor & Francis. 188-189.

Reynolds, Matt. "DNA analysis reveals that Yetis are actually a bunch of different bears". Wired, Nov 2017.

Izzard, R. (1955). The Abominable Snowman Adventure. Hodder and Staoughton.

Lan, T.; Gill, S.; Bellemain, E.; Bischof, R.; Zawaz, M.A.; Lindqvist, C. (2017). "Evolutionary history of enigmatic bears in the Tibetan Plateau-Himalaya region and the identity of the yeti". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 284 (1868): 20171804. doi:10.1098/rspb.2017.1804. PMC 5740279. PMID 29187630.

Milligan, L. (1990). The "Truth" about the Bigfoot Legend. Western Folklore, 49(1), 83-98.

Sykes, B. C., Mullis, R. A., Hagenmuller, C., Melton, T. W., & Sartori, M. (2014). Genetic analysis of hair samples attributed to yeti, bigfoot and other anomalous primates. Proceedings: Biological Sciences, 281(1789), 1-3.

Scientific Name: Lutra nippon

Status: Once widespread in Japan, in 2012 they were declared extinct. In the 1800s, animals were hunted for pelts as they were a very profitable export, and there was a seemingly endless supply in the myriad rivers. Even after protections were put into place, pollution and human development prevented the last lingering populations from recovering.

The Ainu say that a forgetful person is called an "otter-head", and this is a reference to the fact that otters would frequently catch a fish, eat a few bites, get distracted, and then forget entirely about their meal, leaving it to waste. The spirit of an otter can also possess a person, and when that happens, memory suffers. When the fresh and half-finished repast of an otter is found, a person can consume it, but only after prayers have been said to the goddess of fire to cleanse any taint of otter spirit from the fish.

When the Creator first made animals, river otter was instructed to make red clothing for foxes. But because otter was so forgetful, he made the skin white. Fox was unhappy with this color. After upbraiding otter for his lapse, the two of them went to the stream. Otter caught a salmon, mashed up roe, and painted fox a rich red color. Much happier with this new coloration, fox returned the favor by extracting a deep brown from the bark of Shikerebe-ni plant, and used it to dye otter's coat.

References:

Batchelor, J. (1894). Items of Ainu Folk-Lore. The Journal of American Folklore, 7(24), 15-44.